CS 208 f21 — C: Data Representation and Memory Management

Table of Contents

Some of you asked about group work on the introductory survey. Labs 4 and 5 can be done with a partner of your choice (you will also have an opportunity to be matched with a partner). VS Code has a great Live Share extension to help with collaboration.

1 C Arrays (and Strings)

Like many programming languages, C provides fixed-length arrays. These arrays occupy a contiguous chunk of memory with the elements in index order.

int a[6]; // declaration, stored at 0x10 // indexing: a[0] = 0x015f; a[5] = a[0]; // No bounds checking a[6] = 0xbad; // writes to 0x28 a[-1] = 0xbad; // writes to 0xc // an "array" is just a pointer to an element int* p; // stored at 0x40 // these two lines are equivalent p = a; p = &a[0]; // write to a[0] *p = 0xa; // see subsection on strings char str[] = "hi!!!!";

This spreadsheet memory diagram shows one way the above code could affect memory.

Note that this is now a 64-bit example, so memory addresses (and thus the pointer p) are 8 bytes wide.

The row addresses and offsets work the same way as the previous examples, the rows are just 8 bytes instead of 4.

This means the block of 24 bytes holding the 6 int's in the array a takes up 3 adjacent rows.

Trace through the code and study the memory diagram.

1.1 C Strings

As previously mentioned, a C string is simply an array of char (array of 1-byte values) ending with a null terminator (0x00 or '\0').

The terminator value is crucial because otherwise C has no way of knowing where the string ends.

If a string is missing the null terminator, C will keep reading bytes from memory until it happens to encounter 0x00.

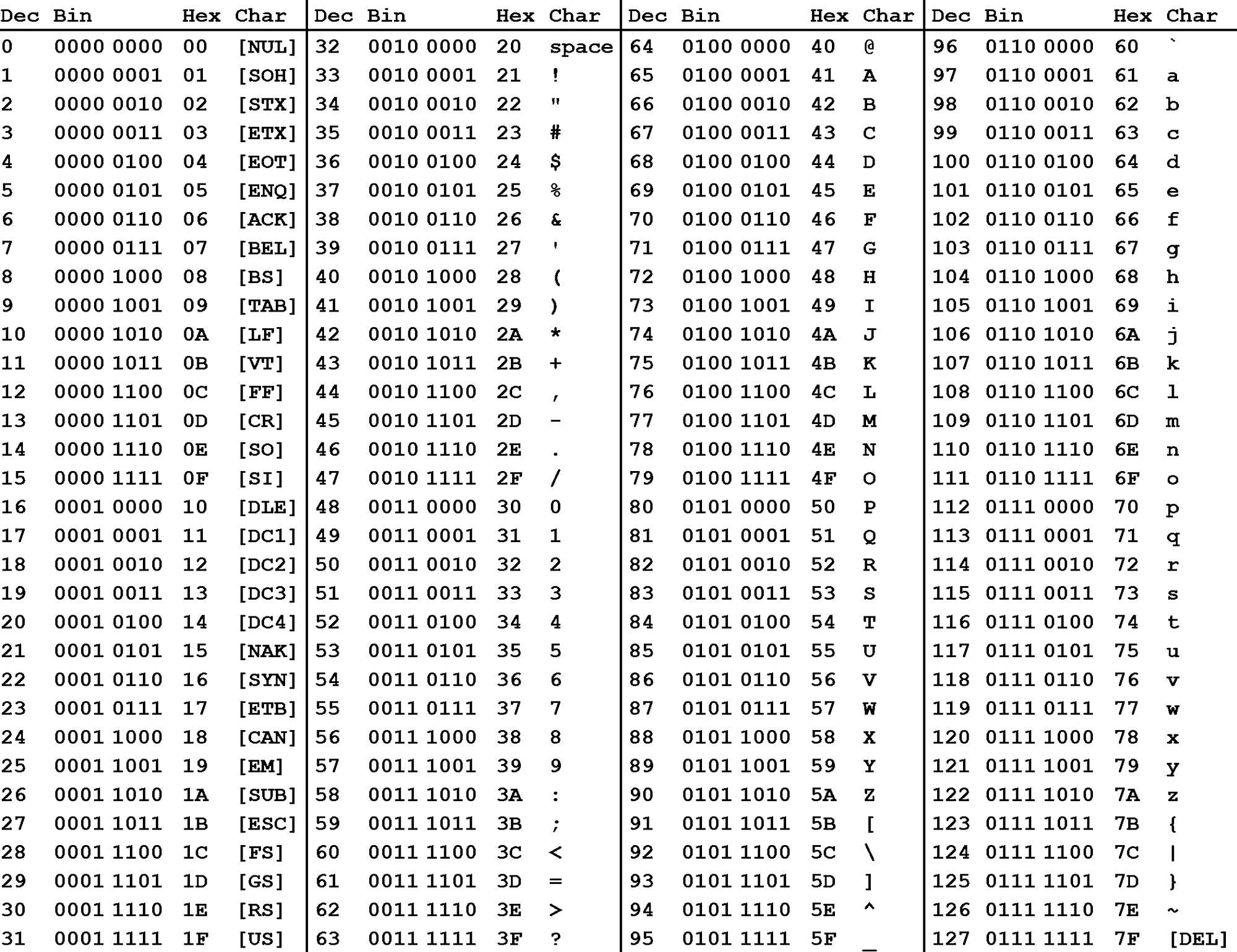

In memory, characters are represented using their ASCII values (American Standard Code for Information Interchange), which has each letter or symbol correspond to a particular hex value (see the table below or run man ascii in your terminal).

Thus, the string "hi!!!!" is represented by the array of bytes

0x68 0x69 0x21 0x21 0x21 0x21 0x00

1.1.1 The C string library

#include <string.h>gives you access to some useful functions for working with C strings- http://cplusplus.com/reference is an excellent source of documentation

strlen(s)returns the length of the string (char *)s, not counting the null terminatorstrcpy(dest, src)copies the string atdesttosrc(both arguments are of typechar *(pointers to the start of achararray)strcpyprovides no protection ifsrcis longer than destination, it will simply overwrite whatever is in memory after the end of thedestarray- fortunately,

strncpylets you provide a maximum number of characters to copy

2 C Structures

While there are no objects in C, the programmer can still create new data types.

The primary way to create data types in C are structures (struct).

A struct is a way of combining different types of data:

struct list_ele { char *value; struct list_ele *next; }; struct queue { struct list_ele *head; }; int main() { struct list_ele node; node.value = "I'm just a humble node"; node.next = NULL; struct queue q; q.head = &node; struct list_ele second; q.head->next = &second; // equivalent to (*q.head).next = &second; }

- variable declarations like any other type:

struct name name1, *pn, name_ar[3]; - access fields with

.or->in the case of the pointer (p->fieldis shorthand for(*p).field) - like arrays, struct elements are stored in a contiguous region with a pointer to the first byte

sizeof(struct list_ele)? 16 bytes (8 bytes for each pointer)- compiler maintains the byte offset information needed to access additional fields

- e.g., the compiler knows that

nextis stored 8 bytes after the start of alist_ele

- e.g., the compiler knows that

3 Practice

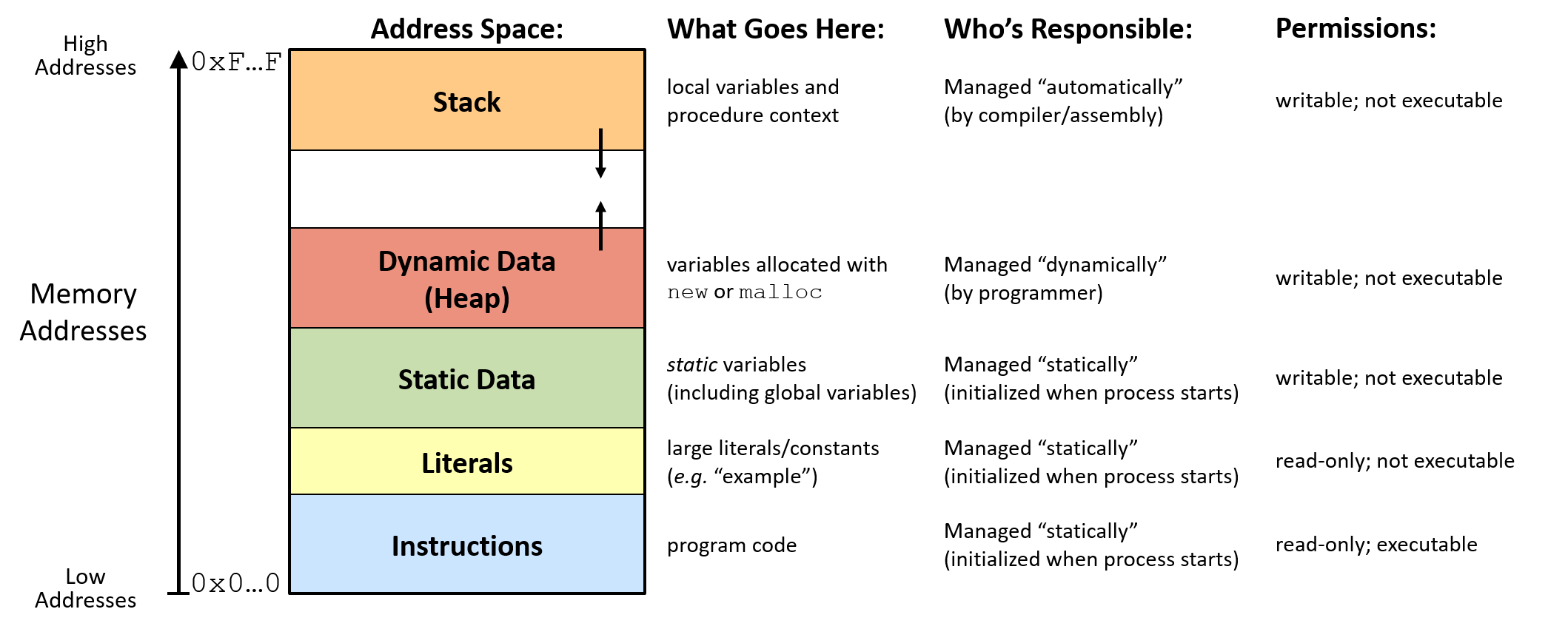

4 Memory Layout

Though memory is a long array of bytes, it is actually separated into various segments or memory regions. Memory allocated at compile time is located on the stack, which resides at high addresses in memory. As more data is added to the stack, the region grows to include lower addresses, so we say the stack grows down.

Memory allocated dynamically using malloc is placed on the heap, which resides somewhere in the middle of memory.

As more data is added to the heap, the region grows to include higher addresses, so we say the heap grows up.

The other three regions (static data, literals, and instructions) are fixed in size and get initialized when a program starts running.

5 Why We Need the Heap

#include <stdlib.h> #include <string.h> typedef struct node { struct node *next; char *value; } Node; typedef struct queue { Node *head; } Queue; void q_add0(Queue q, char *s) { Node n; n.next = NULL; n.value = s; if (q.head) { n.next = q.head; } q.head = &n; } void q_add1(Queue *q, char *s) { Node n; n.next = NULL; n.value = s; if (q->head) { n.next = q->head; } q->head = &n; } void q_add2(Queue *q, char *s) { Node *n = (Node*) malloc(sizeof(Node)); n->next = NULL; n->value = s; if (q->head) { n->next = q->head; } q->head = n; } void q_add3(Queue *q, char *s) { Node *n = (Node*) malloc(sizeof(Node)); n->next = NULL; n->value = (char*) malloc(strlen(s) + 1); strncpy(n->value, s, strlen(s) + 1); if (q->head) { n->next = q->head; } q->head = n; } int main() { Queue q; q.head = NULL; char *s = malloc(30); strcpy(s, "fungi"); q_add0(q, s); // change to q_add1, q_add2, or q_add3 strcpy(s, "balloon"); q_add0(q, s); // change to q_add1, q_add2, or q_add3 }

6 Allocating Memory

There are two ways that memory gets allocated for data storage:

- Compile Time (or static) Allocation

- Memory for named variables is allocated by the compiler

- Exact size and type of storage must be known at compile time

- For standard array declarations, this is why the size has to be constant

- Dynamic Memory Allocation

- Memory allocated "on the fly" during run time

- Dynamically allocated space usually placed in a program segment known as the heap or the free store

- Exact amount of space or number of items does not have to be known by the compiler in advance.

- For dynamic memory allocation, pointers are crucial

7 Dynamic Memory Allocation

- We can dynamically allocate storage space while the program is running, but we cannot create new variable names "on the fly"

- For this reason, dynamic allocation requires two steps:

- Creating the dynamic space.

- Storing its address in a pointer (so that the space can be accesed)

- To dynamically allocate memory in C, we use the

mallocfunction provided bystdlib.hmalloctakes in a number of bytes to allocate and returns a pointer to the newly allocated spacemallocdoes not do any initialization, so the contents of this memory can be whatever was last written to those bytes- this means you must always perform initialization on memory return by

malloc

- this means you must always perform initialization on memory return by

- De-allocation:

- Deallocation is the "clean-up" of space being used for variables or other data storage

- Compile time variables are automatically deallocated based on their known extent

- It is the programmer's job to deallocate dynamically created space

- To de-allocate dynamic memory, we use the

freefunction operatorfreetakes a pointer that was previously returned bymallocand makes that memory available for future allocationfreehas undefined behavior is used with a pointer that wasn't returned bymallocor a pointer that was already freed

8 typedef

It's common to use typedef to give the struct type a more concise alias.

A typedef statement introduces a shorthand name for a type. The syntax is…

typedef <type> <name>;

The following defines Fraction type to be the type (struct fraction).

C is case sensitive, so fraction is different from Fraction.

It's convenient to use typedef to create types with upper case names and use the lower-case version of the same word as a variable.

typedef struct fraction Fraction; Fraction fraction; // Declare the variable "fraction" of type "Fraction" // which is really just a synonym for "struct fraction".

The following typedef defines the name Tree as a standard pointer to a binary tree node where each node contains some data and "smaller" and "larger" subtree pointers.

typedef struct treenode* Tree; struct treenode { int data; Tree smaller, larger; // equivalently, this line could say }; // "struct treenode *smaller, *larger"

9 Passing a struct

struct foo { long id; char arr[11]; }; char get(struct foo f, int i) { return f.arr[i]; } char get_v2(struct foo *f, int i) { return f->arr[i]; } char set(struct foo f, int i, char v) { return f.arr[i] = v; } char set_v2(struct foo *f, int i, char v) { return f->arr[i] = v; } int main() { struct foo x = {42, {'h', 'e', 'l', 'l', 'o', 'c', 's', '2', '0', '8', '\0'}}; char c = get(x, 4); char c2 = get_v2(&x, 4); set(x, 1, '@'); set_v2(&x, 1, '@'); }

This example shows the importance of using a pointer to pass a struct to a function rather than passing the struct itself.

I've created a struct foo that contains a long and an array of 11 char.

There's a function get that takes a struct foo and an index, and returns the char at that index.

There's another function set that takes a struct foo, an index, and a char and sets the char at that index.

There are two versions of each of these functions, one that takes a struct foo and one that takes at struct foo*.

Notice how with get, passing a struct foo results in the entire structure being copied.

With set, it doesn't even work when passing a struct foo because the modification is done to the local copy.

10 Bringing It All Together

Here's an extended example playing around with a struct and heap vs stack allocation.

Plug in into C Tutor or compile and run it yourself.

/* A demonstration of pointers and pass-by-value semantics in C * CS 208 * Aaron Bauer, Carleton College * compile with "gcc -Og -g -o point_test point_test.c" * to get consistent address values, run with "setarch x86_64 -R ./point_test" */ #include <stdio.h> #include <stdlib.h> typedef struct point { int x; int y; } point_t; void f(point_t p) { p.x++; printf("\nf: &p = %p\n", &p); // different address than &p in main, p has been copied printf("f: p = (%d, %d)\n\n", p.x, p.y); } void g(point_t *q) { q->x++; printf("\ng: &q = %p\n", &q); // different address than &q in main, q has been copied printf("g: q = %p\n", q); // but the value of q is the same (same heap address), the structure hasn't been copied printf("g: q = (%d, %d)\n\n", q->x, q->y); } int main() { // code stored at low addresses printf("&main = %p\n", &main); printf("&f = %p\n", &f); printf("&g = %p\n\n", &g); // p is stack-allocated (does not use malloc) point_t p = {5, 6}; printf("&p = %p\n", &p); printf("p = (%d, %d)\n", p.x, p.y); f(p); printf("p = (%d, %d)\n\n", p.x, p.y); // mutation in f does not affect p, as p was copied point_t *q = (point_t*)malloc(sizeof(point_t)); q->x = 3; // q->x is shorthand for (*q).x q->y = 4; printf("&q = %p\n", &q); // q is stack-allocated, &q is high in memory printf("q = %p\n", q); // q points to heap data, so it's value is a much lower address (higher than code) printf("q = (%d, %d)\n", q->x, q->y); g(q); printf("q = (%d, %d)\n", q->x, q->y); // mutation in g affects *q, same heap address in main and g free(q); printf("q = (%d, %d)\n", q->x, q->y); // undefined behavior to access freed memory }

Footnotes:

an array of three strings would be declared by char *str_array[3];. This would only allocate space for the three pointers, however, not for the strings themselves. You could use malloc to allocate space on the heap for the actual char arrays.

It would take 12 bytes: 11 characters at 1 byte each, plus the null terminator

struct point { int x; int y; };