CS 208 s22 — Bits, Byte Ordering, and C Pointers

Table of Contents

1 Bits in Memory

One of the key reasons we use the C programming language in this course is because it lets the programmer get close to memory (and we're interested in what's going on in memory). This means that, unlike Java or Python, the operations you do in C correspond closely to the underlying arrangement of data in memory. This has some benefits and some serious drawbacks, which I'll discuss in a bit. Before we get to C programming itself, we'll start by going through what memory is and how it's arranged.

1.1 Memory is a Long Array of Bytes

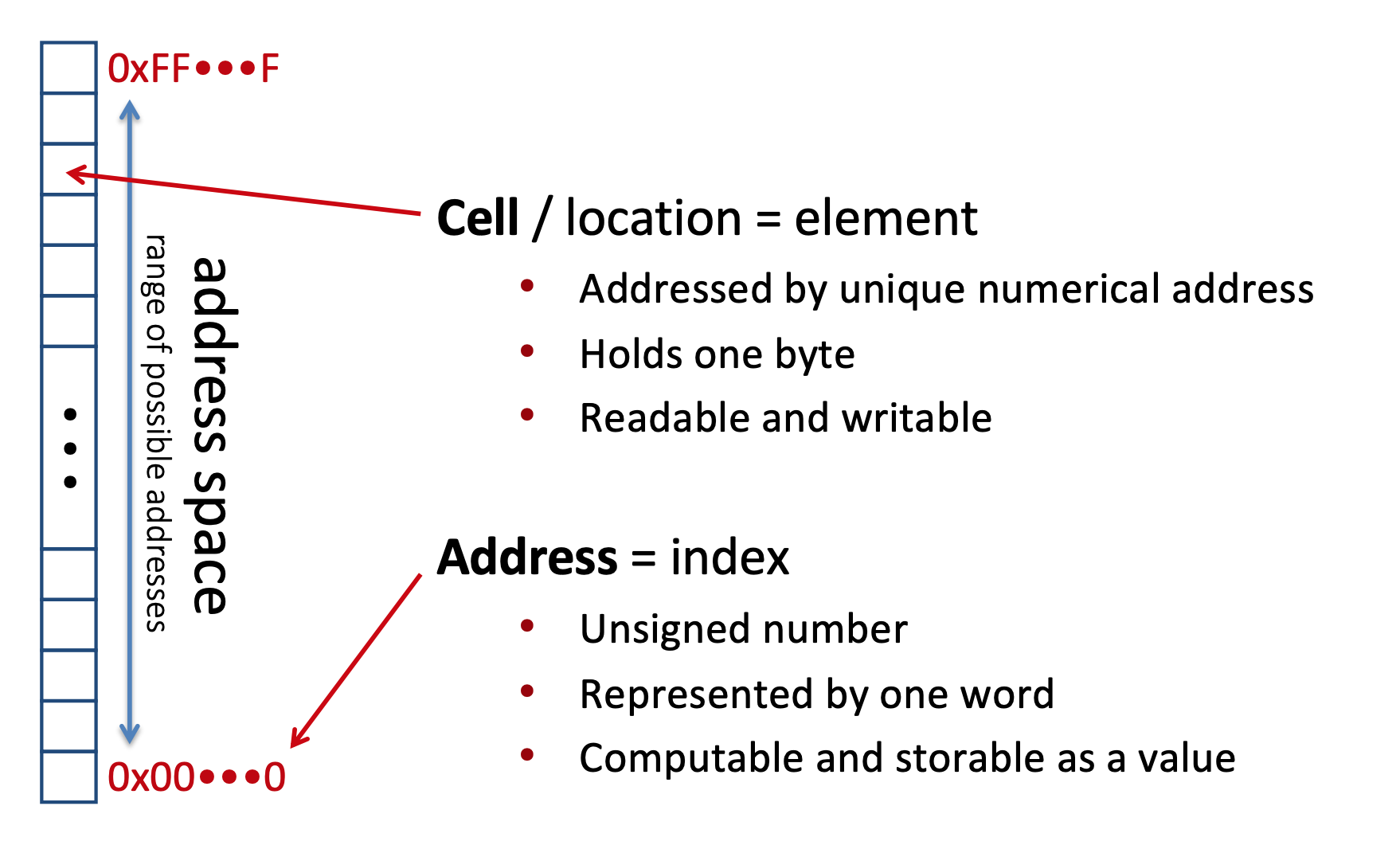

- we will conceive of memory as one giant array of cells or locations, each of which can store one byte (8 bits) of data

- the index or location of a byte in memory is called its memory address

- a memory address, like an array index, is just a number identifying a position within the array of bytes

- where do these addresses come from? how big can they be (i.e., how long is our array of bytes)?

- the organization of a system's memory is based on the word size

- among other things, the word size defines the number of bytes in a memory address

- all memory addresses will be this same fixed length

- the size of a memory address determines the number of possible addresses

- the address space is the amount of memory that can be given addresses

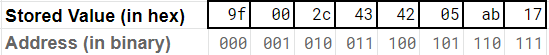

- EXAMPLE: let's bring this together by considering a very small memory

- in this example, memory addresses (and the word size) are 3 bits

- 3 bits give 8 unique combinations, and thus 8 unique memory addresses (i.e., locations for a byte in memory)

- so we say that the address space for this memory is 8 bytes—we have enough unique addresses to refer to a total of 8 different locations/bytes

- modern systems use 64-bit (8-byte) words, for a potential address space of \(2^{64}\) bytes = 18 billion billion bytes = 18 exabytes

1.2 data sizes

- not all data consists of just a single byte

- for example, a C

intis 32 bits/4 bytes wide- what address should we use?

- any chunk of memory is addressed using the first byte (i.e., lowest memory address)

- just like we saw that the bit pattern

0x4e6f21had many different interpretations, the interpretation of data at a memory address depends on both the address and the size

| C type | bytes (32-bit) | bytes (64-bit) |

|---|---|---|

bool |

1 | 1 |

char |

1 | 1 |

short |

2 | 2 |

int |

4 | 4 |

long |

4 | 8 |

char * |

4 | 8 |

int * |

4 | 8 |

float |

4 | 4 |

double |

8 | 8 |

- so a

charstored at memory address0x100would consist of just the single byte at0x100

2 Referring to Bytes

We have some terminology for referring to bytes or bits within a particular piece of data. Specifically, we will refer to the bit in the 1s place as the least significant bit. If we were to write out a binary number, the least significant bit would be the right-most digit. Similarly, we will refer to the bit in the largest place as the most significant bit. This would be the left-most one in a written-out binary number.

We will use this same terminology to refer to bytes within a multi-byte quantity like an int.

For example, in the int 0x0002459f, 0x00 is the most significant byte, while 0x9f is the least significant.

We would say 0x0002 are the two most significant bytes and 0x459f are the two least significant.

3 Byte Order

- ok, so we know an

intat0x100consists of the four bytes at0x100,0x101,0x102, and0x103- let's say our

inthas the value0x2ab600b—which byte goes at which address? - this depends on the system we're working on (the system's endianness)

- let's say our

- if the system stores the least significant byte first, we say it is little endian

- used by x86 (i.e., Intel machines), Andriod, iOS

| address | byte |

|---|---|

0x103 |

2a |

0x102 |

b6 |

0x101 |

60 |

0x100 |

0b |

- if the system stores the most significant byte first, we say it is big endian

- used by networks, Oracle, IBM

| address | byte |

|---|---|

0x103 |

0b |

0x102 |

60 |

0x101 |

b6 |

0x100 |

2a |

- little endian vs big endian is simply a convention or preference, no empirical reason to prefer one over the other

- why the difference then? In the early days of computing, different system designers made different decisions

- it would be nice if everyone could get together and pick one, but it turns out coordination is hard

- why the difference then? In the early days of computing, different system designers made different decisions

- programmer doesn't need to care in most cases

- it matters when data being sent between machines with different endianness

- will need to keep little-endian ordering in mind once we start working with x86-64 assembly

4 Bits and Bytes Practice

- if our word size is 4 bits, how big is our address space? (how many different bytes can we refer to with the set of possible addresses) 1

- if the word size of a machine is 64-bits, which of the following is usually true? (pick all that apply) 2

- 64 bits is the size of a memory address

- 64 bits is the size of an integer

- true or false: by looking at the bits stored in memory, I can tell if a particular 4 bytes is being used to represent an integer, floating point number, or string 3

- for an

intstored at addressx100, which bytes would it consist of (i.e., which range of memory addresses)? 4 - We store the value

0x01020304as a word at address0x100in a big-endian, 64-bit machine. What is the byte of data stored at address0x103?5- Note: I have left off any leading zeros for this value

5 Why C?

5.1 Why learn C?

- It helps you think like an actual computer (abstraction close to machine level) without dealing with raw machine code

- You'll understand just how much Your Favorite Language provides

- C is still widely used

- C's pitfalls still fuel devastating reliability and security failures today (modern relevance, after a sense)

5.2 Why not use C?

- Probably not the right language for your next personal project

- It "gets out of the programmer's way" even when the programmer is unwittingly running toward a cliff

- Advances in programming language design have produced languages that fix C's problems while keeping its strengths

- Rust is a good example

6 Pointers

6.1 First look

Take a look at this spreadsheet-based Memory diagram. First I'll go over how to read the diagram:

- I've taken a section of memory 40-bytes long (address

0x00to0x27) and laid it out as a grid- 10 rows of 4 bytes each

- Each row goes from left to right, so to read all the bytes in consecutive order, you would follow a zig-zag pattern

- left to right on the bottom row, then back to the left byte of the next row up, and so on

- The address of the first byte in each row is shown along the left-most column

- Along the top is shown a byte offset

- To get the address of a particular byte/spreadsheet cell, take the row address to the left and add the byte offset for the column

- So the 4 bytes in the bottom row are at addresses

0x00,0x01(0x00+0x01),0x02(0x00+0x02), and0x03(0x00+0x03) - The 4 bytes on the row above that are at

0x04(0x04+0x00),0x04(0x04+0x01),0x06(0x04+0x02), and0x07(0x04+0x03)

- So the 4 bytes in the bottom row are at addresses

Next, let's go through the values in the diagram and what they mean:

- This is a 32-bit example, meaning that the memory addresses are 32-bit (4 bytes) wide

- I'm using little-endian byte ordering

- The number 496 is stored at address 0x20 (

240 = 0x1f0 = 0xf0 01 00 f0using little endian) - A pointer stored at address

0x08and points to the contents at address0x20 - A pointer to a pointer is stored at address

0x00 - The number 12 is stored at address

0x10. Is it a pointer? How do we know values are pointers or not?- Remember: everything is bits, what the value at

0x10means depends on interpretation/context

- Remember: everything is bits, what the value at

6.2 C example

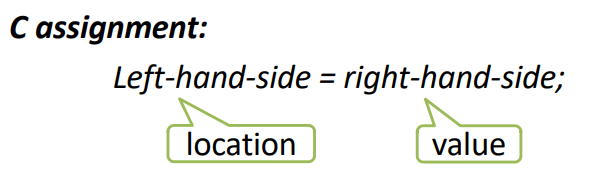

In C, think of assignment statements as having the above structure: a memory location on the left and a value to write to that location on the right.

int* p; // p: 0x04 int x = 5; // x: 0x14, store 5 at 0x14 int y = 2; // y: 0x24, store 2 at 0x24 p = &x; // store 0x14 at 0x04 // load the contents at 0x04 (0x14) // load the contents at 0x14 (0x5) // add 1 and store sum at 0x24 y = 1 + *p; // load the contents at 0x04 (0x14) // store 0xF0 (240) at 0x14 *p = 240;

Here's a memory diagram to go along with the example code above. Again, I am using a 32-bit word size. Trace through the C code and make sure you understand how this code makes the changes between the top and bottom diagrams.

6.3 C mystery 6

What will be printed?

int a = 10; int b = 20; int *pa = &a; a += 5; int *pb = &b; *pa = *pb - *pa; *pb += a; printf("a = %d b = %d\n", a, b);

6.4 Practice

- CSPP practice problem 2.5 (p. 48)

- Exercises 3 and 11 from the w3resource C Pointer practice problems

Footnotes:

With 4-bit addresses, our address space is 16 bytes. This is because 4 bits provide \(2^4 = 16\) unique values.

only 64 bits is the size of a memory address is true, the word size does not directly determine the size of an integer

FALSE, bits alone do not determine what is stored there. The system or a program can interpret them in various ways.

an int takes 4 bytes and the address of a piece of data is always the lowest address, so an int at 0x100 would consist of the four bytes 0x100, 0x101, 0x102, and 0x103.

Since we are on a 64-bit machine, 0x1020304 is actually 0x0000000001020304 when you write out all 64 bits.

Big endian means that the four most significant bytes, all 0x00, will be stored in 0x100 to 0x103, followed by 0x01 02 03 04 in 0x104 to 0x107.

Thus, the byte in 0x103 will be 0x00.

It will print a = 5 b = 25. Visualize the code using C Tutor if you want to see how this happens.